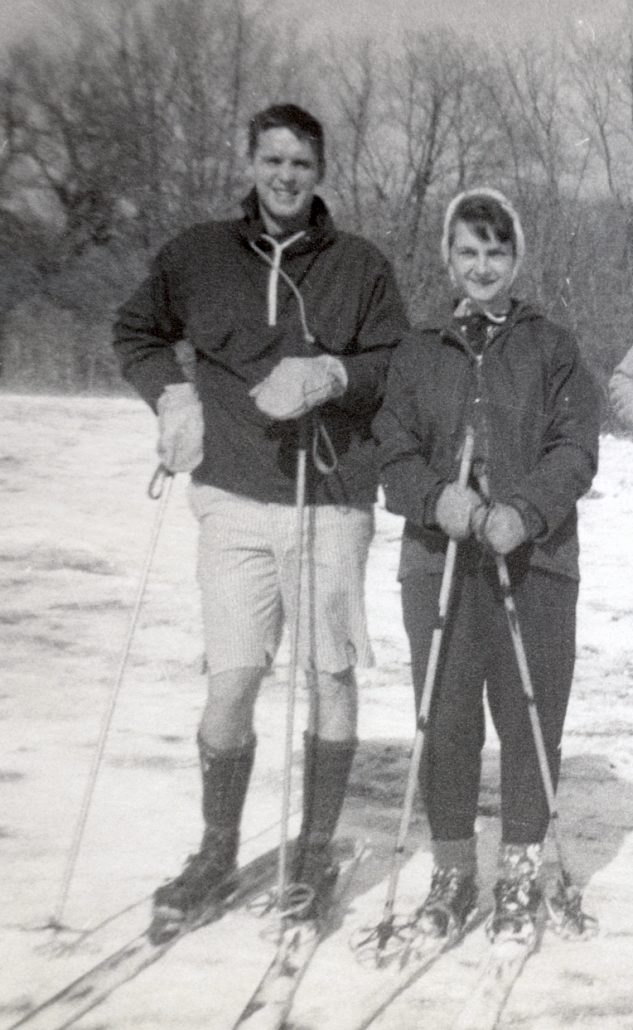

Bruce and Barbara Cole ’59

An interview with Bruce and Barbara Cole from the Class of 1959.

Interviewer: Kit Harrington

Interviewer: Kit Harrington

Marlboro College: I’m Kit Harrington, and I’m interviewing …

Bruce: Bruce and Barbara Cole.

MC: What day is it?

Bruce: December 7th, Pearl Harbor Day.

MC: Today is December 7th! Wonderful. Time flies, huh? All right. So, I was wondering if you guys could tell us a little about where you were and what you were doing before you came to Marlboro.

Bruce: I was in the Service, the Korean War, for a couple of years. And I was eligible for the GI, and need a place to go to school. And I had a brother-in-law that was teaching at Belmont Hill, and he suggested Marlboro College, and I came and visited. And that was in 1955.

Barbara: And I was—I guess I was in Boston at the time. I’d gone to UNH, and to BU, and then for a half a year, and then did some secretarial training and such, and was working for Manpower for awhile.

And then— had known Bruce, we’d met in 1950 in the Angell Memorial Animal Hospital in Boston, where we both worked summer jobs, and we had ended up dating and going to, you know seeing each other, so it was sort of natural that we kept going together and ended up getting married, and I came up in 1956. We were married in ’56. And then uh, came to Marlboro that fall.

MC: What was Marlboro like when you first came—in terms of the structure of the school, and … what did it look like back then—dorm, dining hall …?

Bruce: The basic—the basic dining hall, Dalrymple, outdoor program, that—and the administration—those houses were the nucleus at that point, and, but the first building, the first—yeah, the new building—was Howland House, that was the first new building I think on the college. All the other buildings were part of the original farm. And Howland House —the dormitory for the girls—was the first building.

Barbara: No, Howland came after, because you were—roomed with David.

Bruce: Right, but it was Howland—

Barbara: And then he graduated, it was Howland.

Bruce: No. David Howland’s father gave the money for Howland House.

Barbara: Yeah, but that was when we graduated. Wasn’t it?

Bruce: Yeah, ok.

Barbara: I think, yeah. They were where the nurses’… thing. The girls’ dorm, was down—what’s it called—where the nurses …

MC: The THC? The Total Health Center?

Barbara: Yeah … and then, the boys’ dorm was Mather. And you were on the third floor.

Bruce: The Apple Tree. The Apple Tree was the other original building.

Barbara: But that wasn’t a dorm. No. There were just two dorms.

MC: Was there still farming going on at the time?

Barbara: No. No. The apple trees were good, though, at least we used to make cider from them … those ones by the— well, further, is down next to the Apple Tree building now.

Bruce: But there was no farming—I don’t think there was a farm left in Marlboro at that point. The remnants of a farm—buildings, characteristic of farm buildings—but that was, they were filled with kids, college kids, rather than animals.

MC: Yeah … Marlboro certainly was—was unique then as it is now. What was it like coming and seeing the campus for the first time and being there and realizing just how small and sort of, uh …

MC: So how long did you live in this house, Bruce?

Bruce: 1960. We bought it in 1960.

MC: So how did it feel coming to Marlboro, and seeing it as you guys just described it?

Barbara (to Bruce): Well, you came first.

Bruce: I came first, and there were very few of us. I mean, we had one dorm, that was Mather, and … I lived on the third floor, with a roommate, and there were two kids on the other side of it—I think that’s where Kevin’s office is now – and there were—then the second floor had boys in it, and then the first floor had boys in it, and that was the total capacity of the college.

There was an administration building, and there was a girls’ dorm, and that was—and we had a very informal, as it still is, dining hall, where it currently is, even in 2005, and there were three tables I think we set up for lunch and dinner, and that was it, and the activities were minimal, in terms of offerings, not quite the array of things that go on now. But no, it was—I was comfortable.

Barbara: Yeah … I had come from a small town, but had gone to school in Boston, so I was used to more of a—an outside—well, you know. But still, I had my own horse, and things like that, so coming to a rural area was ok, you know; my uncle had a farm just up the street.

But no, I came as a married person, so it was a little different, I think, in the sense that we had certain goals together. And we—once I came, we lived where Betsy MacArthur lives now, and Katherine Payton was the religion teacher, and we lived with her on South Road, a white house there. And we stayed there for one year, and then the second year we went to John MacArthur’s house, because he was going away for a year with his family to MIT.

So that was the second—they’d gotten electricity the year – that fall, I guess, which was very nice—no kerosene lamps to deal with. But we had wood fire, and everything, so we trudged our way up there the second year, and then the third year we only had half a year left, to finish, so we ended up going back to Katherine Payton’s house for that.

But it was nice, we—I enjoyed very much having the small classes, and—I mean there were five in our graduating class, and Bruce and I comprised two-fifths of it.

Bridget Bennet, now’s Bridget Gorton, and she—Audrey was her mother, and she was—she taught Spanish, English Novel, or two or three other courses, you know, and I think the English Novel had the most people.

Bruce: We’re going back—these interviewers don’t know these people, and obviously they don’t know the graduating class of fifty years ago either. But the only people that are still around that if we say their names you might remember them are John MacArthur and Dick Judd. And maybe Edmund Brelsford, and Veronica—and that’s about it. That are still living in Marlboro.

Barbara: But I don’t think Veronica and Edmund were there when we were.

Bruce: No, no, they came, but they’ve taught for thirty-five years there, forty years.

Barbara: Right, but as students we didn’t have them.

Bruce: No, right. And I think the caliber—the caliber of the kids has remained—there’s an interesting group of kids, whether its way back then or coming in now. It seems like Marlboro tracks interesting characters—students.

MC: I was just going to ask—something you mentioned earlier, about the transition from small town to Boston, to coming back to rural—what are the kinds of things that—I mean before you had electricity—you guys did for fun, after hours, after studying. I understand that it was different for you guys, but in a general sense …

Barbara: Well, we cut wood. There was a work program, of course, on Thursdays, I think it was after every—every Thursday afternoon, we had something to do to work around the college. Because it was only Don Woodard, was the only maintenance person. And his dog, Babe, always with him. So we had that, and I’m trying to think what we …

Bruce: Well, there was a whole operation in the spring, which revolved around sugaring, that no longer takes place. But the Monday night lectures, I remember that as sort of a social thing, and people were brought in to stimulate the students.

Barbara: Yeah, and Tuesday, we had, with Dick Judd, we had that seminar for the education program …

Bruce: Yeah, but that was a class.

Barbara: Tuesday nights. Well, yeah, but that takes up time.

Bruce: But, yeah. There was a lot of social interaction, within the group of—whether it was thirty-five or forty of us, we would—what do you say, hang out together, whether it was up in Dalrymple or studying.

I think that there was a lot of focus on studying. I mean obviously we had parties and that situation existed then as it does now, I’m sure. But obviously much more going on now in the recreational aspect.

We didn’t have an outdoor program such as now. We had our own ski tow though, which you guys don’t have now, down on the left as you come—down by the parking lot, by the music building, we had our own truck engine and a ski tow, and we did cross-country skiing and downhill. So there were certainly activities going on, but …

Barbara: Well, you and I worked also. We worked for the forester, Alsey Hicks, and we went out for a dollar an hour. And we went to areas around southern Vermont— Londonderry, and Guilford and around, and we went either planting trees or pruning white pine, which they don’t do anymore, but you’d get up on a ladder and prune sixteen feet up.

I think there is, in the archives, there’s some pictures of us, out there. Tony Cucciaro was one of them up there, and myself, I think, in one of the pictures.

So that took, you know, some of our time. Because we had to work, we had to put ourselves through college, so. And you had a scholarship from your Unitarian Universalists …

Bruce: Yeah, I had the GI Bill, which obviously many kids did at that point—

Barbara: I didn’t have anything.

Bruce: And we were able to do things then that you probably couldn’t do nowadays, in terms of supplementing your income. I suppose you could still work your way through college, nowadays, but it’s much more difficult, we could manage it a little—and there were scholarships available and Marlboro was generous. And we didn’t end up owing anybody anything when we graduated, which I think was kind of …

Barbara: Yeah. Well, I think Katherine charged us, what, a hundred thirty-five dollars a semester? For …

Bruce: Room and board, yeah.

Barbara: Not board. We paid two dollars for …

Bruce: Well we worked for her, though, in exchange, you know.

Barbara: Yeah, brought the wood in and …

Bruce: But a lot of kids nowadays I think live with faculty members or live with other families, rather than live on campus they live with—have other arrangements, especially if the dorms are filled.

And we liked the community; and not only was the college community exciting, and interesting, but the village of Marlboro and the people in it—unique, I think.

Barbara: One of the things I think when we first got married was that we decided we didn’t want to live in the suburbs. You know, and didn’t want to do that same pattern that we saw everyone around us going, Oh, Lord.

Bruce: We knew what we didn’t want to do, but we still don’t know what we want to do, but that’s beside the point.

Barbara: It worked out well.

MC: Did you go down to Brattleboro at all?

Barbara: Yeah … it took us how many minutes in David Howland’s car?

Bruce: Well the trouble is not going down, it was getting back.

Before we got married, I was going down to Boston, or Canton, and I’d have to hitchhike both ways, and getting down wasn’t bad, but coming back on Sunday, I can tell you I’ve slept in the old train station, because I couldn’t get—if I came in Sunday night, nothing happened after seven o’clock on Sunday night, and there was an eight o’clock bus that would go up to the college from Brattleboro, so I would sleep in the train station if I could, and then grab the bus and get back to college.

Or I’d walk—if I ever could get a ride hitchhiking, I’d get to the end of South Road, and then of course no one was going down South Road, so I’d have to walk the last three miles. Yeah, Brattleboro was the focus, as it still is, and it was the Friday night trip, and you know, it was movies, and yeah.

MC: Did you feel very isolated, up at Marlboro, from the rest of the world?

Barbara: No. I didn’t. We were busy. We had enough to do, you know.

Bruce: No, I didn’t miss anything, I don’t think, from the outside world.

MC: How did the campus change while you were there? In terms of—what sort of role did you play, in changing the college, whether new buildings, you were talking about Howland being built …?

Bruce: Well, actually we were more of a maintenance crew … we were trying to keep them up, and together and painted if you wish … We did, as Barbara mentioned, every Thursday afternoon there was a three or four-hour work crew, and there were projects to do, and therefore you had perhaps a greater feeling of what maintaining the physical structures, because they at that point didn’t have any money to pay the faculty rather than even think of building a building.

And this—that first building that was built was a generous gift from Weston Howland, who was a trustee of the college, and therefore the first building happened the year we ’59. And before that there wasn’t a new building built on the campus, it was still utilizing the old farm and those various buildings.

But subsequently, because we have stayed in contact with the college, we’ve seen the Music School association necessitated the building of the music—the concert hall, so that that was well in advance of anything that Marlboro College could see as a need, but because of the association between the Marlboro College and the Marlboro Music School, there was a— – there was a push to build it, obviously, so that the summer school could use it.

And then there was the library, because Dalrymple used to be the library, upstairs in the … and then, we saw some more dorms, and then we saw the coffee shop, and—but the old, the old outdoor program is still in the—we call it the blacksmith shop. And then I remember the house raising— we did a house raising for the student union building …

Barbara: Well I think—aren’t we going back to some of your first sentences? It gave us a sense of ownership, so that you— it sort of instilled more a sense of really belonging to the college, and the college belonged to you, so that you took responsibility—perhaps more responsibility for what happened, and what is happening.

Well not now, as much, because we’re not there as often, but, you know it was our college, we hammered the floor down in the dining room, and you dug the ditch for the septic, I remember there’re some pictures of that still around; so that, together, there was a very cohesive, I would say a very cohesive group of individuals living there. Teachers, students …

Bruce: And the faculty, the faculty was very unique as it still is. The type of people who came: the Dick Judds, the Roland Boydens, the John MacArthurs, those people that came and were part of it in its development, and then as it started to grow, and obviously it always seems to be on the brink of financial crisis.

And hopefully it’s less now than it was, but now some of the issues are just compounded; you’ve got a bigger student body, a bigger faculty, and comes with that. Faculties expect more—some of the faculty when we were there weren’t even taking salary, or if they did it was very minimal, but different type of teacher, or professor, if you will.

Barbara: Well, they can’t afford to do that nowadays, with the prices of things.

Bruce: No, no. Not as a rule. But some faculty probably still …

Barbara: Yes, they could, I suppose.

MC: Could you talk a little more about the faculty, maybe Dick Judd or John MacArthur, and the student-faculty relationship at the time?

Bruce: Unique. Yeah.

Barbara: Yes. I just felt that you could of course talk to them at any time, and they were right there for you a lot, as friends as well as – I shouldn’t call them peers, because—but in a sense they were the same. I mean, we were, John MacArthur isn’t much older than we are, actually, well, ten years maybe …

Bruce: Always accessible. I mean, they were always available for you, there was …

Barbara: Yeah. You could go to their house, or call them. First-name basis, of course, and they were exciting to study with, because they were learning things as well, you know with you, and I know we didn’t—we had a comprehensive exam that we had to pass, so we didn’t have the—we had tutorials after that, after the sophomore year.

Bruce: Nothing was the Plan, that you people are blessed with.

Barbara: No, we did have to have an area of concentration, we had, and so there were a couple … we did biology, ours was biology and you did history, I think.

And so I worked with John MacArthur’s mother, Olive. And yeah, when she—actually, when we first knew that we were going to have our first child, I told Olive first, rather than my mother, and your mother.

So it was a kind of a warm relationship there, and she gave me her loom, and taught me how to weave, and so, when she —was dying, and she had given me the loom that she had woven so many things on, and so that was kind of nice. And I still have that.

So there was a family relationship, really, I think, with all of them. And we were up at Dick’s a lot with Sue, and Audrey, of course, was on campus, and Audrey’s daughter was in our class, so that made it even more …

Bruce: Of course, the other factor is that we stayed after college so that we—I taught at the school, the little Marlboro school, for twenty-eight years, so I had a lot of the faculty kids in—over the years. So you developed a different relationship with the parents—the faculty—and their kids.

And we felt then a part—although we lived in Wilmington, we were certainly involved with Marlboro, and had the same wavelength, I think you could say.

Barbara: Our hearts are in Marlboro. Our bodies are here.

Bruce: Oh yeah, we—physically the house was available, so we got it. In fact, John MacArthur came up here with me to look at the house. He was in Pennsylvania, we walked up in the snow and looked at the house because it was vacant, and there were two—this house and another house, and John said, “This looks pretty good,” so this is the one we bought.

Barbara: It was funny—we relied entirely on John’s sticking a knife into the beam downstairs and he said, “Yup, seems sound.”

Bruce: Yeah, he said “Okay, looks okay.”

Barbara: And nowadays you have to go through inspectors and all these things … so we kind of lucked out there. But that’s the kind of relationship you’d have, you could call up and say, John, we’re looking at some houses, can you come and he’d say sure, sure I’ll come …

Bruce: Very—unassuming, sort of. I mean, I think some of these people are, were certainly—John MacArthur, I think, could’ve been teaching anywhere.

Barbara: Oh, I think most of them could.

Bruce: And I think Roland Boyden—who was a founder of the college, along with some of the other ’48 and ’49 year—1948 and ’49—I just remember in his class, his being able to make you—there were six or eight or ten of us in the class—and he was able to pose a question and then just—be silent, and wait. Ah, painful.

Barbara: And if you’d done your homework …

Bruce: He was just very, very challenging. And not only with his ability, but just to be able to get stuff out of us. That was just—t was exciting. Hadn’t experienced that before.

MC: It seems like between the close relationship you had with the faculty, and the school in terms of maintenance, it created a much more cohesive educational experience than—than one’s apt to find today.

Bruce: We never felt that—“We’re paying tuition, why do we have to do this work?” But I think you might find that nowadays, that when you’re paying 30,000 or whatever, 28,000 dollars to go to school, you know, “We’re not going to work—paint buildings,” and I don’t know whether that’s part of it or not, and maybe it’s just the general outlook of things.

The pace is different, perhaps, 2005 versus fifty years ago. The rush is greater now perhaps. I think there was a much calmer pace, of our surroundings at Marlboro—not that it’s changed dramatically, but it certainly has changed.

Barbara: Well, many more classes being offered, of course. I mean, you’ve got a much broader curriculum now. And that in itself spreads people out more.

Bruce: Yeah, but my contention is with education, the offerings are certainly important, and where do you end with what you can offer in a university or a college? I think it’s up to the individual students, that you are able to elect and select, and staff or faculty that is willing to let them pursue their interests with the suggestions and advice of a faculty member. Because—the bottom line is, its up to the individual student, really, as to what he or she gets out of—

-phone rings-

Barbara: Good grief. [ … ] Anyway … Now, you were somewhere—in the middle of a sentence.

Bruce: Oh, I was just expounding on the ability of students to make or break their career. I mean, it’s up to the students how much they get out of it or how much they put into it. And that’s very difficult for a professor or any teacher to provide that if the student isn’t receptive, so. And I think the climate is there at Marlboro College to have that interaction between faculty and students, which is unique.

Ah, I just think of the students that go through the college, and some of them—we’ve known over the years. We used to get quite a few students that would come to the school and help in various capacities.

And a lot of the students stay around, so you see them and uh—in various success stories, if you wish—they’re all success stories, or most of them are, so … But we certainly enjoyed being able to associate, after we’d graduated, with the college and see its growth.

And—being—after working in the bookstore for ten years on a part-time, very part-time basis, it’s still the same feeling, that we had when we were there as students. Kids are excited, challenged, frustrated, lazy sometimes, but— wonderful. Wonderful group of kids. Very impressed.

MC: How about Walter Hendricks?

Barbara: I don’t know him.

Bruce: I only get what I read, and the name rings—you know, mostly negative. No, I think Walter Hendricks was unique among founders of colleges, because he must have been able to found, one in Germany, one in Marlboro, one in Brattleboro, one in—Putney …

Ah, the last Potash Hill, I think, had a good article of his association with Robert Frost, and how they were able to do what they did, and Frost I guess was at the first graduating class, and … I assume that he was—had the knack to start a school, and perhaps had financial difficulties along the way, but he certainly was able to not only make Marlboro successful to a certain degree, as he did with Windham College, as he did with Landmark, as he did with the college in Germany …

His family is still in the area; in fact, the college I think just purchased recently some land that belonged to his son. So …

Barbara: I just never—I didn’t know him at all. He was gone when we came—or at least, we didn’t have anything to do with him, so …

Bruce: Well, we knew he’d gone to Brattleboro, and – no, he went to Windham. Windham College.

MC: My mother went to Windham College for a couple of years, and so I find Walter Hendricks and—what he’s done— to be, you know, quite an interesting phenomenon. I wonder, did you hear many stories, from the faculty or—about him?

Barbara: No.

Bruce: I never …

Barbara: I think well, the other night, I went to—you didn’t go, because you had done your hip—I went to the Pioneer dinner, and they were talking about him—or that was in the library I guess, we were doing another round of recordings, and people were discussing Walter at that point, and they said that at one of the selectboard meetings, or at one of the Town Meetings, they had actually fired him, but it didn’t come to pass.

Bruce: Well I think it was—it was financial, though, I think, more than anything? The way he—

Barbara: I think so. But that was … so no, Walter’s …

MC: How about Town Meetings? What were those like, for you?

Barbara: Oh those were great. Because everybody spoke—you know, the teachers and—well they had to, there weren’t enough people to … go around, you know. It was – I don’t know if we had all the different committees you have now, but people voiced their opinions, and it was just a grand—run about the same.

Bruce: It was, you know the student court, the selectpeople, that was—are still part of—people, I know the bookstore was closed on Town Meeting day, so one of us would go to—whoever was working that day—we would go down to the Town Meeting. And it was crowded.

Barbara: But you’re talking about now.

Bruce: Now, nowadays. But I’m just saying it was similar—even though there were only thirty or forty of us, way back,— same sort of issues, with laundromat— still hear things about the washing machine, and the dryer downstairs, so there are issues of—money, but yeah, it was—a strong feeling, I think, of being able to speak your piece in front of the whole group. It was good.

MC: Being able to participate in the governance of the school, did that affect how you saw your place at Marlboro?

Bruce: Well I think Barbara alluded to it earlier, you became more— it was—you had a hand in your own destiny. That you could see the issues right up front, whether it was a new faculty member coming, or a new bus that you were thinking of being able to purchase, because—and you just felt you were part of it. And that doesn’t happen too often in institutions of higher learning, I don’t think.

Barbara: No, no.

MC: Today, even today, Marlboro is obviously such a unique experience and it seems like it was even more so when you guys were attending. At the time, when you were going to Marlboro, how did you see Marlboro as different and unique –—or looking back on it?

Barbara: Oh, I’d gone to UNH and sat in a biology class of like, almost 500 students and if your seat was filled, you’d get a check mark that you’d gone there. I also lived in a women’s dorm that you had to be in at 10:30 at night, and checked in, and it was all—no males were allowed anywhere near the dorm.

So it was like—you know, going, well not a private school thing, or boarding school, but it was similar. So that was a different scene for me, and then BU of course was in the middle of Boston, but that I commuted from home, but then it lived too far out.

So that was different there, you know, as far as … I also, you know, I taught at Marlboro. For a year. I taught—well, right after – it was in ’67. ’66? ’67. ’65, ’66, ’67, in through there, and they were searching for a permanent teacher for biology.

Olive was still alive at the time, and Roland called me, and he said “Barbara, do you—we need someone to teach biology this fall,” and this was summer, and he said “Would you be able to do that?” and I had three children at that point, and they were like eighteen months apart and then twenty-two months apart, so it was like …

And you were teaching at the elementary school, and I kind of nearly fell over, but sort of said “Well, let me talk to Olive, and see,” and I did talk to Olive, and she said, “Well, I do a sort of botany course – introductory botany course,” and I did that.

And it was fun. I had twelve students I think, and we did labs. So that was kind of exciting, and then the next couple of years I helped in the—or at least one more year, I helped in the lab as a lab assistant. So that was kind of a nice role too.

And then our son went to Marlboro. So we’ve had sort of an all-around—you’ve been a trustee, an alumni trustee. So we’re filling all the niches here. No president, though. We don’t want, no thank you.

MC: How much do you think the unique qualities and eccentricities—what made Marlboro Marlboro—was a reflection of the individuals who were there, as opposed to the structure of how the school was run?

Bruce: Well the ones that are successful—I’m thinking of the students—that come to be part of this ongoing process—if they succeed, it’s I think a wonderful experience for them. If they don’t, then someone made a good in having them be accepted. Because the uniqueness is there, for the student, because of the way the faculty functions, and the offerings, and the way that they advance the learning situations of a seventeen, eighteen year old kid who comes out of high school.

Barbara: Well, yeah, the student themselves may want a change from where they are, or whatever, and then realize once they get here that it’s—well as you were talking earlier, there was a child or person that didn’t fit in, or feel that they were getting what they really needed out of it. And there were a lot of people that it won’t be good for.

And so that’s why I would think it would be a very difficult position to be on the admissions [committee], because it’s a lot of lives that you’re dealing with, and a crises situation can arise because you’ve—made a wrong choice, and you know, it’s a big hunk out of someone’s life at that point.

MC: I was curious if you could talk about your son’s experience at Marlboro? Because I hear he was an older student at Marlboro in the early ’90s. What was that like, seeing your son go through the same institution that you had gone through?

Barbara: Oh, it was great. We were working at the bookstore at the time, and actually I was taking some of the same courses he was—I keep going back and taking courses, and so there were a number of the same ones that I was in with him, actually, which was kind of fun. He’d already gone to Johnson for a couple of years and worked for a couple of years, and so as you say, he was a little older, but—he made a lot of good friends, and did well.

Bruce: Yeah, I think his success was because of Jenny Ramstetter, because he was doing his project, or Plan, with Jenny, and she helped—as many of the faculty help the kids through their difficult times, she certainly was instrumental in Andrew being successful.

Barbara: Well he went out and worked on her ranch, for two or three summers out in Colorado, so that’s where he did studies of the prairie and grasslands.

Bruce: Prairie dog. Yeah, we had five—we have five children, and three of them went to UVM—the three girls went to UVM —and the two boys were at Johnson, and Andrew—the last male—wasn’t necessarily ready for Johnson, although he was there for a couple of years or a year and a half and Marlboro was the answer.

And a lot of his success was with Hilly – Hilly van Loon was there, as a counselor – anyway, she was an advisor, I guess, but very helpful, for kids that were – potential kids, but didn’t always appear that way. Or their success in other schools was not apparent, or Marlboro fulfilled their niche.

And that’s I think—a lot of times, transfers to Marlboro are oftentimes very successful after a year or two, obviously here a lot of kids come in—not a lot, but starting as a midterm student, and it’s—I think a place where a lot of kids have found—not a great deal of success at other institutions, and yet Marlboro has been able to help them along.

MC: You spoke earlier—I mean, you’ve talked about what campus life was like and I’m wondering if there are any stories in particular that stick out in your mind. One man I talked to spoke of him and his roommate going to—some caves in the area, spelunking and finding bats? And bringing them back and actually having them in his dorm room for a couple of weeks before—I think John MacArthur came over and said “What are you guys doing!?”

Bruce: Some of the antics, I think—

Barbara: Pranks.

Bruce: Pranks. I remember putting a toilet commode on the top of Dalrymple chimney; I don’t know if that’s been done recently.

Also, if you go into the administration building—I don’t know if that’s the administration building now, the—as you come up to the—it’s that little building—(Admissions). Admissions. I still, there was … there were only two people who ran the college at that point, and we somehow got the key to the place, and there was a trapdoor in the first floor, and we went in one night and moved everything, respectively, downstairs—we opened the trapdoor and put everything neatly down underneath in the cellar, so when they came in the next day they came in, opened the door, and there was just an empty room.

Barbara: Howard Aplen?

Bruce: Yeah, Howard Aplen, and Ramona Cutting, and Roland Boyden’s office, I think, too. So, I think they were harmless to a degree; I remember going off Mather’s—I was on the third floor, and we’d come off—in the winter, we’d come off—out of the third floor, onto the roof of the L, and slide off the roof into the snow banks, that was kind of exciting …

But nothing, nothing that was, you know, destructive beyond —I mean, we could always put the things back upstairs— which we did—and then it was a small enough group so that you were caught with anything you did anyways. You couldn’t really escape.

And I think the sugaring aspect was, was an exciting … A lot of people—one difficulty was that it always came during spring break, but that was—a number of people participated in that, and it was—it was an exciting sort of venture.

Barbara: Yeah, Buck Turner was sort of in charge, I think, of that.

Bruce: Yeah. And I heard the sugar house now is the old pottery studio—the kiln—that was the old sugar house.

Barbara: There are pictures—Kevin’s got one of the pictures of that, and also I’ve got pictures of you coming off the roof, but that may not be a good one to put in.

Bruce: Yeah, and also – we were feeding the fire in the sugar house, and that was ….

In fact, I remember—I’ll send a piece of paper home with you —I wrote, when we were at the bookstore, ten years ago, I wrote—I took a walk into the, with a bunch of faculty, and students, we walked some of the woodland.

And somehow through this process I said, you know, this is a shame that we don’t get this interest, what a way to build a sugar house, and have the kids involved with it, mill the wood, and do the whole works, and involve it with the faculty —the kids could learn all the things that are necessary for the —the botany of sugaring … anyway, I always felt that those are things you remember—at least we remember, we’re still sugaring now. And it certainly began back there …

Barbara: Oh yes, we wouldn’t have sugared, now I don’t think, if we hadn’t learned at the store.

Bruce: And that is something that is very close to us, in that dimension. But you know, things come and go. And again, it’s a commitment if you’re going to do something like that. And you’re here primarily for an education, and sometimes that doesn’t follow into the sequence of what you have in mind.

MC: How about the other students who were attending Marlboro at the time, whether in your class, or classes below or above you; did they have similar backgrounds … were they GIs as well?

Barbara: Oh gosh, I don’t know ….

Bruce: We have kept in contact with the kids – before us, or after us, or during us – primarily through a thing that I really hate, is the Phonathon. And I would – or we would – we’ve always done it for the last fifteen, twenty years; and we would only do it if – with the people that we knew, either before us, during our period, or shortly afterwards.

And we—we’ve been able to, you know, we know a lot of kids that graduated with us—we don’t necessarily—I always would talk to them, trying to get money out of them, but at least I would talk, and touch base, and so …

Barbara: We keep in touch with Sumner and Bridget— because you were his best man, actually, at the wedding.

Bruce: Oh yeah, there’s some of them … but yeah, we made friendships during college that we’re still pursuing, not only with the faculty but also students.

And many of the backgrounds I think were similar; people were looking for a place that would help them pursue a college education. And there were—I don’t think you could peg a certain type of person that came to Marlboro, even back then. There were diverse, I think of the kids—some of them from the city, some of them veterans, some of them, ah, you know, sort of wandering, not sure what they were going to do… yeah, it was strange. But exciting, I thought.

MC: Barbara, for you what was it like being one of the earlier women on campus, one of the first?

Barbara: Well, we had – there was Arden Blake, and Bridget and myself, and Tinkie Turner, uh, Catherine, she lives up the hill now – she married Buck Turner, one of the teachers.

Well, I honestly – coming as a married woman, it makes a whole lot of difference. I wasn’t in the dorm with the girls. I made friends with them, we had classes together and everything, but then Bruce and I would go off to the – to Katherine Payton’s, or John and Margaret’s, or afterwards.

So we weren’t overnight on campus, so we didn’t have the night life there; we had to go home, get dinner; we had a couple of animals, couple of dogs that we had with us—not at Katherine’s, but at John and Margaret’s. And so we had household responsibilities, you know, as well as—so I honestly don’t know, as far as, you know, doing anything with them – we all just did classes together, and ate lunch, and …

MC: In classes, did it feel like —

Barbara: Weird to be married and them not, or …?

MC: Well, that, certainly, or did you feel like having so few women in the school, did that affect —

Barbara: No, I went to an all-girls’ private school, so – (You were happy.) I’ve had a lot of women, in my life. And I had two sisters, and one brother, so I think you know, no, that didn’t, that wasn’t funny …

No, I mean, I had Olive MacArthur as a, you know, a woman teacher, and I don’t know. She was just a very important person in our lives, in my life particularly. So that—and Audrey; thinking of the women teachers that were there; no, I think was perfectly content.

Bruce: You fit in.

Barbara: Yeah, we fit in.

MC: Going back, I guess, a little—as you were—back when you first came to Marlboro, or previous to that, I’m sure you both had certain expectations for what you—thought, or wanted, your college experience to be like. I know you said, you knew what you didn’t want. So, were your expectations, your hopes and fears, were they met at Marlboro?

Barbara: Oh, mine certainly were, yeah.

Bruce: Yeah, but we came to a crash, in ’59, we graduated, and then what do we do? I mean, we were liberal arts graduates—what, where, what’re our—?

So we went to Pennsylvania, I picked up, we went back to get certification credits, so we went to a semester at a state teachers’ college to get the required things to teach, and you didn’t need a master’s at that point, so we moved to Pennsylvania for a couple of years and I taught in high school.

But the—I was interested to hear you say you’d want to go into education, and that was—I mean, that’s great, because I never really had that. Although we did stuff with Dick and Tom, we went to rural schools, and worked—did correcting workbooks and stuff, really trivial stuff. But we got a feeling for school.

And then when fifty—when we graduated, what do we do? I don’t—as I said, I don’t even know at age 72 what I want to do with the rest of my life. Got a lot of things—so you know, I retired. I retired in 1988. I was 55. And I really have not had a job—and don’t, we don’t have an independent income, either. And I haven’t really had a full-time job since 1988.

And I’ve used all of my Marlboro credentials—I’ve got a liberal arts thing from there, I got an honorary—the first honorary master’s is something from Marlboro, and I’ve got two other masters’—and so what do I do now? I paint houses, and mow lawns. So yeah. Who’s to say that—I’m happy, so that whether Marlboro contributed to that or not. I think it did.

Barbara: Oh, I think it did. I think the work ethic is something that—and I think we came with the work ethic, but I also think it helped instill a work ethic in us, that I hope to see at the college now.

I think as Bruce mentioned earlier, there are different factions, but I think they’re probably—you could find a group that—isn’t it this weekend that they’re going to go do the trails or something, I just read that … and—oh, the Ho Chi Minh trail, I guess they were going to do some work on that.

And you’re going to get a group of people that are still, I think, have that dedication to the college. And you’re also going to get people who are here, and utilizing what’s available, and then moving on and not keeping the close ties to it.

But there is – at some point, someone said there is this ring around miles away – that there are people that are all scattered around, but they’re all Marlboro, and they all focus in ….

Bruce: Well, I’m thinking of Jay Craven, and what he’s been able to do, with—not only being a faculty member at the college, but what he’s instilled in students. I’m amazed that—of his followings, that the kids are filming for him and with him, summers, and you know, I think that’s so—important.

I mean, it gives him a real purpose, and what they’re taking, his academic classes, to go out and pursue and edit and do the stuff that as a new—relatively new faculty member, I think it’s great that these things happen.

And I think Marlboro draws some extremely exciting and interesting people, for faculty.

MC: So the work ethic was one of the greatest impacts that you feel Marlboro had on your life.

Barbara: I think, yeah. And that sense of ownership and belonging.

MC: We’ve talked on and off about how Marlboro’s changed over the years and I wonder if you could specifically talk about your impression of that and how you feel about it today.

Bruce: The biggest thing—I don’t see the change. I see physical change, I see a lot of new buildings, I see some beautiful things that are happening—the library addition, and all of the things—the amenities that make it more attractive to prospective students, but I don’t think in purpose—that’s the physical entity of it.

In purpose of its goals, of its philosophy, I don’t think Marlboro’s changed. I think it’s still working in the same avenues that it did way back—many years ago. So you can make all these adjustments physically, and if you those criteria that you had way back, that would be a shame. And Marlboro, I don’t think it has at all lost that—that look of a direction that it wants to go. And I think it still has it.

I don’t know whether the faculty would, in their faculty meetings, would agree to that, they’d probably argue back and forth with vehemence. But I think their underlying—you know, somebody like Tom Toleno’s been around for a long time, and you know, T. Wilson. These people are certainly dedicated, and they see the same future, I think, that they saw in the school thirty years ago.

Kids are a little different, perhaps, maybe smarter, maybe more worldly. But I think their goals are still the same, I don’t think the faculty changed too much to what they wanted to accomplish with kids.

Barbara: I think it’s hard sometimes to see the thread continuing through. And I think the longevity of some of these people that are on campus now, that as Bruce just that help to sort—well, have the continuity, but the stabilizing effect, and then they up and down, bouncing off of it, and not everything’s going to happen, I think there was some—quite a bit of discussion about the road out back.

And the committees to try to save the woods, and not do this expansion, and then the building, or the community, I mean the college itself, the growth of it would—I shouldn’t say a hodgepodge of buildings, but there’s certainly a variety of architectural styles on campus now that I think, from my perspective, I remember the little college on the hill with the farmhouses, and then suddenly I see these things coming up and I’m thinking, “Is this really Marlboro?” And what’s happened to Marlboro that’s caused the need for this, you know. And I don’t know what’s caused the need for that. But I do know that I think it has a lot to do with who’s in charge, and who gets the architects in and say, you know ….

Bruce: And who gets the money.

Barbara: Because I remember being in the bookstore and two of the architects came in, before they built the addition to Mumford House, and they said, “Well, we want something that looks Vermont,” so they were looking for barns and whatever, and I think they were from Canada. And then they were all dressed appropriately for New York City.

And we showed them a few things that we had, but then I see what they did, you know, just stainless steel or whatever’s on the side, and it just – I don’t know, it bothered me a little bit, I think, to see some of the changes. But I know that in order to be keeping up with the times, perhaps you need to provide what some of the other colleges are providing, in the sense … and yet, maybe you don’t. Maybe you could stay where you are, and people will come to you because of what you were, or what you have.

Bruce: There was always an argument as to where the—number crunch, where do you get—I think we’re at 300, and I can remember 200, a 100 was even astronomical in the thought process. And I don’t think the growing pain has diluted—I mean, I think 300 is a teeny—you’re talking ten thousand kids at a school, or five thousand, I don’t think 300 is—is—I would not—where is that magic number, and that’s a topic of conversation that probably will go on forever. And we got to 300, or 310, or whatever—

Barbara: It’s more than that. What is it now?

MC: 350 maybe?

Bruce: Is it 350?

Barbara: Yeah, because I remember they told the trustees, “Oh, well, we’re not going to go above 300.”

Bruce: Well, I think, that is the thing that is probably not the scariest, but that’s something that the budget people, the trustees …

And I think that’s another important issue the trustees I can remember, the library, Walter Whitehill, who was in charge of the Boston Atheneum, his description of—I think the library, his part of the library, it was named after him—he wanted a Vermont farmhouse with “a roomful of books.”

Barbara: With a fireplace.

Bruce: Which they never used. But I mean, his concept of that, with many fireplaces, they never—I think they were afraid the kids would burn the books, but—

Barbara: Well yeah. Late night, “Oh, the fire’s going down, we don’t need these pages …”

Bruce: But I think that in many organizations the trustees, or the CEOs—the trustees at Marlboro have always been an interesting group.

One of the recent presidents—Ted Wendell, of the trustees— was a former student—not a student, he taught. Way, way back—he taught a math class, and went to – he was from Harvard, and graduated—did he ever graduate from Marlboro? Anyways, he still comes back for the Wendell Cup, it’s a cross-country race.

He was president of the trustees for three or four years, I think very financially beneficial, and helpful, and all of—I knew the trustees when I was an alumni trustee, and that perpetuates the feeling of Marlboro. Because you’re not going to bring people on that think Marlborois kooky. You want people that have money, and also think that Marlboro’s doing a good job. And those people—I think Morris Pecket—a doctor, he’s been on for probably thirty years. Maybe he’s retired now.

But you know, those people are—I can always remember, once in a while in the spring or the fall there’d be these older people, mainly men, but more women now, on campus. Who are these people?

They’re the trustees. And I think they’re the hidden mechanism of the organization; I think that they’re very instrumental, and I can remember a Town Meeting issue that dealt with the trustees—I think it was the building, and but I think the trustees would come to the meeting because of the concerns, and—that doesn’t happen very often.

MC: Sorry to interrupt you guys, but I only have about three minutes of tape left, so if you want to ask a wrap-up question or something….

MC: All right. Having been part of the school for so many years, do you – did you, and do you feel you were a part of making history, and are you currently?

Barbara: I suppose, in the sense that our bodies are on campus a lot, and … yeah, I mean I think just feeding into it … I think that one of the things that I’ve enjoyed doing is going back for many years and taking classes; working beside students and knowing, you know, a lot of art, a lot of biology. And I’ve got at least thirty, forty more credits I think.

Bruce: We’re a living example of people that went there and are still very involved with it and certainly wish to support it more financially, obviously, and we do in kind—we work in the Phonathon and we do things that we can say we’re contributing. We do minimally give money, but you know, we still have a feeling that it’s viable, valuable, yeah. I think it’s got a place.

Barbara: Yeah, and I think that as you asked, are we part of it —yes. Because we—we’re still connected.

I think working in the bookstore has been very good for both of us too, for getting to keep a connection. You know, I don’t like to be too far away. We go to the lectures, we go to the plays—and right now, I’m busy with these puppies, so I’m not going anywhere, but—

Bruce: I also think that it offered me, in the short period of time, or the way I dealt for twenty-eight years with kids, I liked, I wanted to. And I think, going into teaching, maybe you’ll be able to incorporate, even with youngsters, some of the things that you were offered.

Barbara: Yeah. And the way you were taught in classes.

MC: Is there any last things you’d like to say about Marlboro? This has just been wonderful, to hear you …

Barbara: Thank you, well, it’s wonderful that you’re doing this; we appreciate that a great deal too, I think, because it helps to perpetuate the, you know …

Bruce: Yeah, well, I think it’s important because this is the archives. I mean, fifty years from now, you can look at this and say “Boy.”

Barbara: Those old people.

Bruce: Thank you.

MC: Thank you so much.

Bruce: We’ll come and when you finish this we’ll come and take a look at this … (hands piece of paper) Wrote ten years ago and it deals with the sugaring thing and how it could be implemented into the curriculum and Engel could do some stuff with it and Ramstetter could and Tober could write economic plans for the—you know?

MC: You know, what’s so cool is that one of the things I’m learning about in education is Dewey’s whole philosophy of connecting education and experience, and it seems like this, this would sort of be instrumental …

Barbara: Oh yeah, yeah.

Bruce: Well, hands-on; it was something that …

Barbara: Yeah. And you’re doing what you’ve learned.

MC: And I feel like that is so key, having something—you know, learning things that you can really apply to the rest of your life.

Barbara: I taught environmental science K-6 for many years, here at about 13, I guess, and we did have the five kids so I was only about three-fifths time. But I had, you know, kindergarteners through sixth graders, and it was great; I got them outdoors, sifting soil, and doing all sorts of hands-on things, we did science—instead of just out of a book, I got them outdoors …